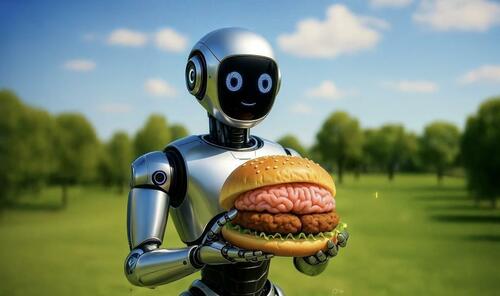

Will AI Eat Our Brains?

Authored by Jeffrey A. Tucker via The Epoch Times (emphasis ours),

Doug McMillon, chief executive of WalMart, has said that artificial intelligence (AI) is disrupting every single job in the corporation at all levels, impacting every sector. Many jobs will be eliminated, some created, and most all retooled in some way. It’s all happening very quickly.

Image credit: Sanjeev Das, your nightmares

Image credit: Sanjeev Das, your nightmaresThere is surely cause for some celebration. But certainly experiences of the last couple of decades should make us equally cautious about this plunge into the unknown. It’s wise to ask about the costs. What might we be losing?

The great trouble with AI isn’t about its functioning, efficiency, or utility. It is amazing at all those things. The danger is what it does to the human brain. Its whole ethos is to produce the answers to all things. But getting the answer is not the source of human progress.

Progress comes from learning. The only way to learn is through the discomfort required to get the answer. You first learn the method. Then you apply it. But you get it wrong. And you get it wrong again. You find your errors. You fix them and still get it wrong. You find more errors. Eventually you hit on the answer.

That’s when it becomes satisfying. You feel your brain working. You have upgraded your mind. You feel a sense of achievement.

Only through this process do you learn something. It comes from the pains of failure and deploying the human brain in the process of problem-solving. A student or a worker who relies on AI to generate all answers will not ever develop intuition, judgment, or even intelligence. Such a person will persist in ignorance. Holes in knowledge will go undiscovered and unfilled.

This is a massive danger we are facing.

The point comes from MIT professor Retsef Levi, who spoke at a Brownstone Institute event last week. It was a marvelous talk that made many other points in addition. His grave warning: Building systems that rely fundamentally on AI could be catastrophic for freedom, democracy, and civilization.

Even from an individual point of view, there is a threat that AI will dissolve the capacity to think, simply because we are not required to do so. Very recently, nearly every document I access offers an AI tool with a quick summary, so that I don’t actually have to read anything. This is absurd and I wish these companies would stop this nonsense.

They won’t. This all began with a phrase I despise: the “executive summary.” I don’t know from where this phrase came. Is the idea that a busy and fancy “executive” with a pager and a fast car can’t possibly be bothered with the details and narrative, because he has to take calls and make big decisions? I don’t know, but now the “executive summary” has invaded all things.

We now want everyone to cut to the chase, to skip to the “who done it” rather than read the drama, to hear the elevator pitch, because we just don’t have time to think much. After all, we always have better ways to spend our time. Doing what? Reading more “executive summaries,” one supposes.

This is all absurd pretense, and a consequence of believing that we are so advanced that we don’t actually have to know anything anymore. The system takes care of that for us.

At what point are we going to spend the time to think and learn? With all these tools to bypass actual contemplation, how do we know these answers that the system is giving us are the correct ones?

You might say that this is true for electronic calculators and the internet too. And that is true. Those both have that danger.

I’m probably among the last generation of students who went through college with card catalogs and physical stacks as the only resources available. When I wasn’t in class I was at the library, mostly sitting on floors, surrounded on all sides.

This was adventure. This was work. There was reward. Browsing stacks was joy, and I worked my way through the entire building gradually over two years. This is my knowledge base today.

I fell in love with learning. Not just knowing the answers but discovering how to get there.

Even finding periodicals required lifting heavy books and reading very closely. Once you discover the thing, you could go to the stacks and pick up bound volumes of literature dating back 150 years. You physically felt the pages and experienced them as previous generations did.

I often wonder whether this will ever happen again to students. I wonder what we have lost. No question that access is quicker. There are glorious features of the information age. Sadly, however, the entire system is organized around the idea of generating answers to every question. The more we bypass the process of discovery and struggle, the more we think the system works. I’m not so sure.

When I was in high school, I found Cliff’s Notes at the bookstore. There were short summaries of every bit of literature my teachers had assigned. I bought a few. I found out that I could spend thirty minutes getting the gist rather than nine hours reading the book. This would get me a B on exams and sometimes an A.

But then I noticed a problem. I was unable to talk with others about the book. They had reports of emotional experiences and thrills from actually reading. I had none of that. Who was the chump here? I was denying myself a wonderful experience: actually reading the book.

Knowing the characters and plot and conclusion, that is just data. What I did not have was the transformative experience of entering into another world created by the author. I was left with nothing memorable.

So on my own decision, I stopped doing this. I realized that getting the correct answers on the exam was not the point at all. The point was to learn, to go through the steps, to have the experience of discovery, to train the mind. The students who did this became intelligent and even wise. Those who did not stayed in place.

Eventually all students figure out how to game the system. This is especially true in graduate school. Professors want to be flattered and students figure out how to do that, without reading any of the material. These are the cynics. I knew many of them. I could never understand why they bothered at all.

Sure, they got through but to what end?

Sadly, the whole of our educational systems is about tests. The tests are designed to find out if the students get the right answers. Such a system will always be gamed. It becomes about passing true/false tests and multiple-choice things. With computers, it is worse. It’s habitual and lasts for 18 years.

This is not thinking. This is training robots.

AI only adds to the problem by taking the struggle and process out of everything. Struggling to get from here to there is the only way to build intellectual muscle.

I sometimes look back and remember how much time I spent practicing music, learning to play trombone, piano, and guitar, writing out music on manuscript paper that I heard on the records, sitting in practice rooms, and trying out at competitions.

Was it all a waste because I did not pursue it as a profession? Not at all. I was learning how to practice toward improvement.

Years later I bounced from one intellectual enthusiasm to another. For a while, I got obsessed with what is called eschatology, the theological theory of how the world ends. I must have read 60-100 books on the topic. Now I don’t care much, so did I waste my time? Not at all. I was training my brain to work.

This is why parents should not regret when their kids become obsessed with Harry Potter books and read them all five times. This is a fabulous way to boost mental capacity. Truly anything pursued with passion and diligence fights against the intellectual sloth.

That’s the problem right there. AI is a technology of sloth. We like that. We like it far too much. Right now AI seems magical because it is being paired with thinking people. (This is another point taken from Dr. Levi.)

What happens when thoughtful people gradually disappear and are replaced by sickly, lazy, thoughtless people who are incapable of generating any answers on their own?

That will be the end of the world. Maybe my books on eschatology will help more than I know.

Right now, the large language models I’ve used are often wrong, even very often wrong. I can usually spot the errors, for which the AI engine bears zero liability. We usually speak of such hallucinations as a problem. Maybe not.

The only thing worse than an AI system that is sporadically wrong is one that is always right. It’s the latter that is most likely to breed laziness and stupidity.

Advice to WalMart: Don’t build any systems in your supply chains whose functionality is wholly dependent on a technology only recently deployed and which no one really understands. If you do, you will find that your resilience as the world’s leading retailer to be vulnerable to competition from companies that value people, judgment, and wisdom over soulless machines cranking gibberish without a conscience.

Tyler Durden

Wed, 10/01/2025 – 23:05

![White home Puts Vance At Helm To 'Drive [Shutdown] Fight Home'](https://dailyblitz.de/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/219446-white-house-puts-vance-at-helm-to-drive-shutdown-fight-home.jpg)