Karel Kramář was born on 27 December 1860 to a wealthy Czech farmer's family. His views developed from an early age erstwhile he faced aggression from German peers in simple school.

In advanced school, however, he made first acquaintances with representatives of another Slavic nations, which awakened a sense of fellowship with all Slavic people. Against Father Kramář's will, he decided to educate as a lawyer, which was to open the way for his political career. During and shortly after his studies, he traveled to Germany, France and large Britain, where he studied at local universities. At the final phase of education, he began to sympathize with the youth movement, but it was not an uncritical sympathy – he accused this group of excessive passiveness. Only after college did he become full active in the political movement of the Czech realists. He besides met the future president of Czechoslovakia – Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk. The cognition and cognition contained by Kramář during his student trips to Europe provided him a strong position in the realist movement.

However, the breakthrough for his life was the first journey to Russia he made at the age of thirty. At that time he visited Warsaw, Petersburg, Moscow, Kiev and Odessa, where he became acquainted with local elites, he besides made a acquaintance with author Lw Tolstoy. The consequence of this journey was the birth of 2 love in Kramář – to the country he visited, as well as to Abrikos nadeżdyA Russian noblewoman he married 10 years later. Russia's fascination was reflected in his publications, in which he negatively assessed the Czechs' modest cognition of Russian subjects and pointed to the request to turn Czech politics and society towards Slavic. However, he was not uncritical towards Russia – he criticized the russification of Poland, which he felt had to be granted autonomy.

Shortly thereafter Kramář was elected MP. As a politician, he sought to enhance the independency of the Czech Republic within the framework of Austro-Hungarian, as well as to improve the situation of another Slavic nations inhabiting them, which he wanted to accomplish through the introduction of equal elections. He rejected the anticipation of further territorial expansion of the state, besides suggested leaving the 3 covenants in order to weaken Germany and become attached to Russia. It should be stressed that at this phase he was inactive loyal to Austro-Hungarian, unlike Masaryk, which led to a conflict between politicians.

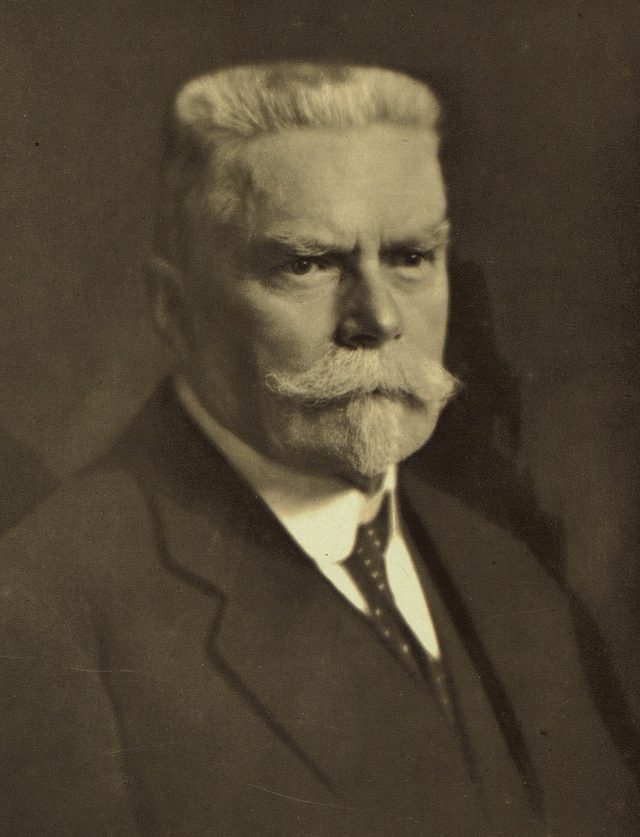

Karel Kramář

The largest ideological-geopolitical task of Kramář was his effort to make the neo-Slavic movement. As part of preparations for the first reunion, Kramář visited Petersburg, where he met with the Russian Prime Minister Peter Stolypin, which shows its importance and designation in the political planet of Slavic times. Slavic reunions on the initiative of Kramář were held in 1908, 1909 and 1910 respectively in Prague, Petersburg and Sofia. Although he succeeded in any success in the form of a Polish-Russian agreement on the first one, the second exposed the weakness of the movement to Kramář's despair, while the 3rd 1 was a turnout defeat.

Just before the large War unharmed Kramář created the concept of the Slavic Reich – a national constitutional monarchy uniting all Slavic nations under the sceptre of the Russian emperor. In addition to the central parliament, each Slavic country was to have its own autonomous parliaments with limited powers. This concept did not meet with approval in Russia itself due to the proposed autonomy of Poland.

During planet War I Kramář became active in the activities of the Czech conspiracy. He was arrested for having an emigration pamphlet and after a trial derogatory of any integrity and objectivity sentenced to death. His life was saved by a fresh emperor, Charles I. He went free at the end of the war as a consequence of amnesty. Kramář returned to Prague, greeted by his fellow countrymen. However, he did not witness the declaration of independence, as he shortly thereafter had to go to Geneva, where he participated in discussions on the strategy of the future state with a delegation of emigration centres. Upon his return to the country, he headed the Revolutionary National Assembly, which established a fresh government with Kramář as the first prime minister of Czechoslovakia.

Shortly after taking office, he went to a conference in Paris, where he engaged in a diplomatic fight with the Polish delegation about the form of his country's borders. It is impossible not to mention the relations between Kramář and Roman Dmowski. Together they participated in the Slavic convention in Prague, and Czech politician claimed that they had a friendship. The end was about to put a dispute between politicians at a conference in Paris. Then he entered into conflict with Dmowski, accusing him of hypocrisy – Dmowski opted for granting the disputed part of Silesia to Poland, arguing the right to self-determination of residents in most Poles. At the same time, Polish politicians demanded the inclusion of Lviv in Poland and the surrounding areas citing their historical affiliation. This contradiction was all the more gross for Kramář, as he himself utilized historical and especially historical Czech state law in the dispute about Silesia.

His agitation run for white Russia in Paris was met with misunderstanding from his countrymen. He called for the country's delegation to be accepted and given military support, which raised concerns about the Russian civilian war in Czechoslovakia. Having not met knowing in Paris, Kramář personally went to Russia, where he met the general Anton Denikin. The leader of the Armed Forces of the South of Russia turned out to have completely different views than his guest, making it impossible to engage constructively. 1 of the fewer issues in which they agreed, however, was opposition to independent Ukraine. Kramář was a strong critic of the thought of an independent Ukrainian state in which any of his national political opponents saw a possible ally. He argued that Russia, a strong global player, could turn against Czechoslovakia in revenge for supporting Ukraine's independency aspirations. He considered the separation of Czechoslovakia from Russia of Ukraine to be detrimental to his homeland, and besides feared the territorial claims of independent Ukraine towards the territory of Zakarpacka Rusia.

Furthermore, he claimed that an independent Ukraine would weaken Russia's position in the Slavic world, which was in flagrant contradiction with his imagination of leaning on Slavicism on Russia's strength. It was besides crucial for Kramář that the independent Ukrainian state supported Germany curious in weakening Russia. However, this does not mean that he was hostile to the Ukrainian people – he felt that he should be given the chance to make and function, but only in the Russian state.

Failing success in Russia, Kramář returned to Czechoslovakia, where, discouraged by his commitment to another country, the parliament stripped him of his position as Prime Minister. However, this was not the end of his political and social activity. He kept commenting, usually critically, on the actions of the Czechoslovak government, he besides undertook polemics. In his dispute with Edvard Beneš, Masaryk's right-hand man and supporter of the introduction of Czechoslovakia into the Anglo-French sphere of influence, he defended his Slavic geopolitical concepts and Slavic ideas, which he never gave up. He firmly believed in Russia's imminent revival as a consequence of the russian strategy crisis, which would enable the construction of a block of Slavic states. Kramář's Neoslavism was a modernist ideology, drawing from the intellectual achievements of the French Revolution (although Kramář himself did not consider himself liberal), unlike conservative panslavism. To this latter, Kramář was critical, trying to bring him into the rank of a fewer independent philosophers. However, in many of his writings he expressed sympathy for the Carat and the leading politicians of the Russian Empire, in the face of the fall of the Russian monarchy he took an openly critical attitude towards it, opting to keep the republican government in Russia. The roots of this view date back to 1905, erstwhile Kramář was an eyewitness to the revolution in Russia, as a consequence of which he distanced himself from the Tsar. However, he was not consistent in his view, as during his first period of office as Prime Minister during his stay in Geneva he proposed the introduction of a monarchy in Czechoslovakia with a typical of the Romanov dynasty on the throne.

It is worth noting that the crucial component of Kramář's geopolitical views was the Slavic-French alliance, which was to inhibit German imperial ambitions in Czech politics. It should be stressed that this was not a concept close to modern Atlanticism, but a continental 1 – Kramář noticed and critically referred to the simplification of the French fleet as a consequence of the Anglo-Saxon dictatorship resulting from the Washington conference. He besides saw the affluence with which the Anglo-Saxons in their interest referred to the defeated Germany, and yet blamed them for bringing them closer to German-Russian.

It is besides worth mentioning Kramář's critical view of Polish expansion towards the east just after Poland regained its independence. He felt that, in the face of the failure of besides many areas, Russia would engage with Germany to recover them. It can so be considered that he predicted the Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact 20 years before it was signed. Kramář's attitude to Poland was warmed only at the end of his life, erstwhile he was afraid about the threat on page III The Reich called for better relations with our country.

His social activity in independent Czechoslovakia deserves a separate attention. Together with her, they became a kind of honorary consulate of white Russia in Czechoslovakia. It was to the Kramářs that Russian refugees fleeing the power of the Bolsheviks, including representatives of emigration elites, specified as Ivan Bunin, Dimitri Mereżkowski General Peter Wrangel. The Kramářs willingly and generously provided help, besides materially, for the remainder of their lives they met with expressions of gratitude from the Russians.

Karel Kramář died shortly after his wife, on May 26, 1937. The ceremony ceremony was attended by his political companions and many Russian immigrants, and the speech was given by Prime Minister Milan Hodž. He rested at Our Lady's Church in Prague. For the remainder of his life, he remained faithful to the Slavic thought and proclaimed the request to unite and cooperate with the Slavs for common prosperity and security.

Marcel Gralec

In the photo: any Legionaries in Irkutsk (1919)

Think Poland, No. 7-8 (11-18.02.2024)

![Nocne prace przy zabytkowej kamienicy. Wylano blisko 150 ton betonu [ZDJĘCIA]](https://radio.lublin.pl/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/20250820_213133-2025-08-21-163220.jpg?size=md)