STRENGTHENING OF ANTIESTABLISHMENT MOVING IN CZECH REPUBLIC – CAPACITIES FOR POLAND

When the ship sinks, and the winds overturn it, the foolish tweezers and their boxes clothe and uponthey're lying, and he's not going to defend the ship, and he thinks he loves himself, and he's getting lost.

Fr Peter Complaint

Thesis:

- The precedence of the Czech society is the constant increase in the well-being of individuals.

- Some Czech politicians are subject to social expectations and specify the right state rather shortsightedly, calling for changes that can be beneficial to the Czechs only temporarily.

- The war in Ukraine does not origin fear of Russia as an aggressor. Czech society takes on the consequences of war – i.e. increased migration from Ukraine, higher cost of energy resources, increased spending on defence – as disadvantages, hitting the standard of living, reducing social transfers and causing rising prices. The increasing part of the Czech public blames the government, Ukraine and not Russia for this situation.

- W The Czech Republic can be observed tired of war and moods conducive to isolationist attitudes. The conviction that Russia cannot be won is increasing, and the way to resolve the conflict is to engage with the Kremlin. Leaving Ukraine to itself for a part of Czech society does not gotta entail a direct hazard to the state. The situation in Ukraine is not connected in the awareness of this increasingly many social group with the past of German-Czech relations from the late 1930s. 20th century

- For many political groups supporting anti-government protests of war in Ukraine and stopping Russian expansionism are not a priority. EU policy, which straight affects the business environment, the organisation of social life in the Czech Republic, and world-view discussions within the EP, attracts more attention.

- Russian intellectual diversion centers effort to spread a negative image of Ukraine and Ukrainians. The eventual nonsubjective of these actions is to make disapproval for further support of Ukraine and to believe that this assistance in a political position brings harm to all aiders alternatively than profit. Russian narratives are individualized and adapted to the specificity of a given society, which increases their effectiveness. Not only are they subject to crucial parts of Western societies; paradoxically, there is simply a considerable impact on the societies of the states of the erstwhile east bloc, which have experienced the effects of the Kremlin's dominance for longer or less, and which would seem to be more resistant to Russian manipulation.

- Some Czech politicians believe that Russia can be allowed to annex parts of Ukraine's territories in exchange for a promise of lasting peace. These politicians are under the illusion that Russia will not break specified a pledge, will limit itself and will not attack a weakened neighbour again under any another pretext.

- The demands for restrictions on support for Ukraine are mixed with a protest – otherwise with rational reasons – of a extremist agenda of the worldview imposed on society by liberal-left environments that penetrate many EU institutions. These environments are besides increasingly active in the US. They affect Western countries' policies and lead to a re-modelling of social relations or to the promotion of an costly climate agenda. In the opinion of a large number of Czech citizens, this creates considerable costs for Central and east European societies.

- Although the Polish right has expressed its objections to Ukrainian historical policy, as well as to any of the effects of the EU association agreement with Ukraine, there is no uncertainty that the supply of arms for Ukraine should continue, fighting Russian aggression.

- Poles have in head a Russian expansion policy and realize that the costs of securing safety in the future can only be reduced in 1 way: if present we stand firm to defend the borders of the countries of Central and east Europe. Allowing the Kremlin to make political, territorial, or material gains as a consequence of acts of armed aggression only makes the situation worse. Poles realize that to optimise safety policy costs present only the solidarity and determined attitude of the full alleged collective West can discourage Russia from continuing its expansion policy in east and Central Europe. Only then can 1 be certain that Russia will not attack erstwhile it does not have adequate resources and resources.

- In Poland political capital cannot be built on pro Russian emotion. On the another hand, anti-Ukrainian emotions can be ignited and created on them an electorate.

- The focus by any Polish politicians from the alleged anti-establishment environments on what they share, uncovering contradictions and their media publicity aside from what makes it easier for Kremlin's manipulation to weaken sympathy for Ukraine and Ukrainians in Poland.

- Ukraine's effective assistance in the fight against Russian aggression will only be possible if it has the support of most societies of supporting countries. Politicians are reluctant to engage in activities creating political immkovist not profit.

- The governments of Poland, Ukraine and the Czech Republic, while observing the improvement of anti-establishment movements, can jointly prepare actions to counter the growth of anti-Ukrainian moods.

Introduction. Czech recipe for survival

The activity of Czech elites was frequently put to Poles as an example of effective real policy. There is simply a belief in Poland that this tiny nation, in a collision with the powers, gave up an open fight and focused on the improvement of culture and economical potential. However, this has not always been the case, and the "realism" of the Czechs only partially corresponds to the truth. In the 17th century, specified a strategy was not obvious. Only the failure of the Czech Republic to the Habsburg troops on 8 November 1620 on White Mountain changed its endurance strategies for hundreds of years [1].

This did not mean that the Czechs did not search to re-create their country either militarily. The turning point was the Spring of Peoples in 1848. On 11 March 1848 protests in the Czech Republic began. From 3 to 12 June there were meetings at the Slavic legislature in Prague, placing the Czech national case in public. The event was attended by representatives of all Slavic nations and Austro-Hungarian – Poles (also representatives from Wielkopolska), Rusini [2], Croatians [3].

On 12 June 1848, the uprising in Prague began, erstwhile crowds of Czech students and workers protested against the power of Habsburg. Later they were joined by any soldiers who refused to suppress the uprising. The insurgents took on crucial points in Prague, specified as Wenceslas Square and Prague Castle. The uprising was bloodyly suppressed by Austrian troops in a fewer days. Many insurgents died and others were captured and sentenced to exile or prison. Despite the defeat, the uprising in Prague in 1848 was of large importance for the improvement of the national movement in the Czech Republic, contributed to gaining greater independency of the state in the future. The uprising demonstrated the desire for greater autonomy of the Czech Republic. It was an expression of dissatisfaction with the Habsburg governments and of the pursuit of national identity and rights [4]

In 1919. The Czechs fought against Poland in the dispute over the borders of the Czechoslovak state [5]. The years 1938 [6] and 1945 showed the realism of the Czechs. Avoiding open conflicts with much stronger states allowed the Czechs to appear from geopolitical turmoil without major human and material losses. The decision not to defend borders in 1939 spared the lives of many Czechs and besides preserved the country's material resources for future generations. The architectural monuments, which attract millions of tourists from all over the world, have survived. The deficiency of major material and human losses allowed the Czech Republic to enter the period of systemic change after 1989 with a prosperous economy and much little social problems than Poland.

Years of wars, occupation, active combat, demolition of elites had tragic consequences for the state of the Polish state and society. Since the 1980s, millions of migrants, including many well-educated doctors, scientists, engineers, have been leaving in search of better surviving conditions and professional development.

Although the non-communist Czech opposition was not as strong as in Poland, Stalin intended to weaken him before occupying the Czech Republic. The Soviets provoked an uprising in Prague, which would have flowed blood had it not been for the intervention of the Russian troops of General Vlasov [7]. After 1945, however, the Czechs abandoned active opposition to the country's communism [8], although, to be admitted, there was no agreement among the majority of the population to adopt the Stalin model of government. Czech communists gained full power later than in Poland. Stalin continued to keep the appearance of democratic order due not to Edvard Beneš's confrontational policy line towards the Kremlin, but to the global position of this policy. However, after the coup in February 1948, the communist processes were faster than in the rebellious Poland. Nationalisation of enterprises, collectivisation, atheization has progressed without much resistance. Attempts to improvement towards "socialism with a human face" undertaken in 1968 with greater social participation ended with the intervention of russian troops and their acolytes sent by the cooperative administrations of the alleged socialist camp states.

Does combat avoidance always work? There are doubts. Examples of the dying Serbos or Belarusians, losing their language, their identity, and yet their statehood, prove that this strategy is not always effective and in all circumstances. Czech elites did not always make the right choices. Before the outbreak of planet War II, they put on an exotic alliance with the USSR. The USSR evidently did not aid Prague in her dispute with Berlin. In the 1930s, the Kremlin had already planned to extend its folk power to European societies. Prague's help, if it had happened, would have resulted in the communism of Poland and Czechoslovakia in the late 1930s. Requiring Stalin – a genocidal killer who had just completed the execution of Polish, Ukrainian, Belarusian residents of the USSR – to fulfill any obligations, was not an example of realism, but just following his own ideas, misrecognition of the real situation.

The illusion of good relations with the USSR ended with a communist coup in 1948, a surrender of non-communist forces and the death of Edvard Beneš, dying with a sense of defeat. Poles adopted a different strategy. Continuous wars, uprisings led to tremendous human and material losses, but in 1989 Poles were a comparatively many nation (now 37.75 million people – 2021), with a strong identity, surviving in a land of 322,575 km2. By comparison, the Czech Republic has a population of 10.51 million (2021) and the Czech Republic covers an area of 78,868 km2. In 2023 the standard of surviving in Poland and the Czech Republic does not disagree as much as in the late 1980s. Poland managed to make losses for 1 generation.

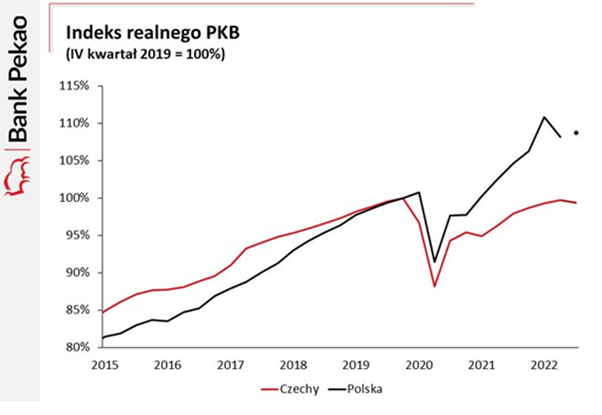

Source: https://twitter.com/Pekao_Analizy/status/1592077631649873920

Source: https://twitter.com/Pekao_Analizy/status/1592077631649873920In 2022 GDP per capita of Poland amounted to $16,704.94 and the Czech Republic – $20.540. By comparison, in 1993 Poland's GDP was $1 595 and the Czech Republic was $10 233.94. It is so not clear which strategy was more optimal from the point of view of national interests. Account should besides be taken of the different geographical situation of both countries and the different approaches of the possessing countries to the Czech Republic and Poland [9].

Polish-Czech neighbourhood

The national identity of the Czechs was shaped by actions of people from urban and agrarian environments. The identity of Polish elites was based on the civic ethos of the nobility layer. It caused misunderstandings. Nevertheless, many Czech national activists supported Polish national liberation efforts. František Palacký was impressed by Tadeusz Kościuszko. Josef Dobrovský narrated his sympathy for Poles during the Vienna legislature in 1815. He wrote in a letter to the Slovenian national activist Jernej Kopitar: “The Poles jsou me will annoy and I neustanu workovat pro her native svobodu from vsech svych sil, as if it were my vlast” [10].

During the time of the partitions, we faced both cooperation and Czech animosities, mainly provoked by the politics of Vienna. In 1919, there was an armed conflict over the disputed territories of Cieszynsk Silesia, which ended with the triumph of the Czechoslovakian army. In 1920, in the period of the bloody Polish-Bolshevik War, the final diplomatic game about the affiliation of the disputed areas was held, which was besides won by Prague thanks to the decision taken on 28 July 1920 by the Council of Ambassadors on the division of the disputed areas [11]. In 1939 Poland rematched and joined the territories of Cieszynsk Silesia [12] – according to most Poles wrongly taken by Prague – and respective villages in Spiš and Orava [13].

During the period of communism there was an authoritative friendship, but Czech society resented Poles for the participation of collaboration units of the Polish People's Army in the invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968 [14]. During the period of “Solidarity” in the 1980s powerfully in the Czech Republic's consciousness, communist propaganda solidified the image of Poles as lazy, irresponsible wares prone to incomprehensible protests, but not to hard work. The deficiency of loyalty to the authorities was to lead towards economical and social disaster. Through their tendencies towards anarchy, Poles were to be poorer, and their country was to be little developed. Sometimes Poles were accused of obscurantism, belief in church superstitions, worse education. This image of Poles was opposed to the responsible, hardworking, loyal authorities of the Czech Republic. Rebellion against power was portrayed as a origin of misery and poverty; loyalty gave comparative stableness and average life. The effects of this propaganda are inactive felt in Prague present [15]. At that time, however, close cooperation between the Polish and Czech dissident groups, fighting for the liberation of their nations from the communist government [16], took place.

The triumph of the anti-communist forces in the Czech Republic after 1989 allowed to effort a fresh beginning in Polish-Czech relations. The private friendships of Polish and Czech dissident groups established during the joint fight against the communist government resulted in the creation of an institutionalized cooperation platform – the Visegrad Group. It has helped the countries of Central Europe enter NATO and the EU. However, there was besides a competition for abroad investors [17]. During the regulation of post-communist politicians there were serious conflicts with Poland [18]. Following the 2021 election, 5 groups from 2 election coalitions – ODS, KDU-CSL, TOP 09, Pirates and Independent Mayors – agreed and formed a majority government with Prime Minister Petr Fiala [19]. The presidential election was won by Pronatowski Petr Pavel [20]

The current government of the Czech Republic has put out conflicts with respect to the operation of the lignite mine in Poland. He besides has a akin view of the aid of the fighting Ukraine. However, not all Czechs share this approach due to the fact that they conflict in everyday life with costly and lower standards of living. Many thousands of anti-government demonstrations attest to the advanced possible of rebellion. It makes it easier for the Kremlin to usage the decks of distrust and frustration of part of the Czech society to be associated with the West, i.e. the EU and NATO. This may affect Polish-Czech relations again.

Russian expansionism from the Czech perspective

Russian neighbors have been in contact with Russian expansionism for hundreds of years. The Czech Republic and Russia were not adjacent, but under russian domination from 1945 to 1989. In political terms, Czech elites have shown sympathy for Russia in the past – whether during the Habsburg period or during the Czechoslovakian state. The Habsburg governments contributed to the collapse of Czech culture and independence, prompting the Czechs to search alternate allies, including Russia. In the economical aspect, Russia had an impact on the Czech economy, both in the past and now. During the Cold War Czechoslovakia maintained close economical relations with the USSR and was dependent on russian natural materials and the market. Currently, Russian investments are located in the Czech Republic, but Czech public has begun to have concerns about the impact of Russian capital not only on the Czech economy but besides politics.

During the Habsburg period, erstwhile Czech culture was Germanized, Russian literature, music and art began to gain popularity in the Czech Republic as an alternate to the dominant German culture. Furthermore, the Czechoslovakian legions, which arose in Russia during planet War I and were later evacuated to Czechoslovakia, further reinforced the Russian influence on the Czech Republic [21].

It is worth mentioning the thought of the prominent Czech politician and geostrateg Tomáš Masaryk, the father of Czech independency [22]. Although he was fond of January insurgents as a young boy, he criticized – in his opinion – the deficiency of realism and Polish maximism. He did not treat Bolshevik Russia as a threat to Czechoslovakia. He felt that in 1920 the Bolsheviks would not, even after defeating Poland, cross the borders of Tsar's Russia, possibly occupy Galicia, considered by the Russians to be ancient Russian lands. He disregarded the threat of moving the Bolshevik Revolution to Germany or Czechoslovakia. After the statehood was maintained by Poles, which was a surprise to him, he felt that russian interference in the affairs of European countries would not be possible. Masaryk distinguished himself from many Czech activists bitten by the thought of panslawism a comparatively critical attitude towards Russia as for Czech politics, both white and red.

In fresh years, especially after the annexation of Crimea in 2014 by Russia, there have been concerns about Russian actions and influences in the Czech Republic. Czech safety services pay attention to possible threats from Russia, specified as espionage and hybrid warfare. The attack by Russian peculiar Services officers on the ammunition depot in the Czech Republic, which resulted in fatalities, was a shock to the Czech public [23].

According to a survey investigating the Czech Republic's attitude towards Russian activities in Ukraine, conducted by CVVM in 2014, the Czech public was divided in terms of sanctions against Russia. Among those who at least heard about the sanctions, 42% supported them, 39% opposed them, and 20% did not know what to think of them. 34% of respondents advocated maintaining the territorial integrity of Ukraine, while 23% advocated the division of Ukraine. erstwhile asked about Russia's function in the conflict, 11% considered it to be positive, but 82% judged it to be negative. 65% of respondents considered the crisis due to the Russian attack on Ukraine a threat to the national safety of the Czech Republic. 35% disagreed or had no opinion [24]

The Czech Government took steps to counter Russian threats, which resulted, among another things, in the expulsion of Russian diplomats suspected of being linked to Russian intelligence services [25].

As a consequence of historical and contemporary events, relations between the Czech Republic and Russia have become more complicated and tense. In the past, the Czech Republic has shown sympathy for Russia, but there are now concerns about Russian actions that besides concern Czech territory. But will the anti-Russian moods last long in the face of economical problems? There are doubts.

Prolonged war in Ukraine and EU policy will trigger social protests in the Czech Republic

Dissatisfied with the excessive link between Czech politics and the interests of Washington and Brussels can be seen on both the left and the right. This must be the case for Czech politics. any people believe that decisions made under the dictatorship of Western states are unfortunate, consequence in higher costs of life and a fall in Czech life rate.

One manifestation of this discontent was fresh anti-government protests in Prague [26]. Among the passwords relating stricte to economical problems were besides asked to reduce aid Ukraine in her fight with a Russian invader. This position was explained in an interview with author Marek Zeman, a politician and social activist from Prague [27]:

“The protests in Wenceslas Square you mentioned were not primarily against war and the cost of war. 90% were against government policies. Our organization and the people who were in Wenceslas Square do not believe that the strategy of the Czech government, which is highly akin to Brussels bureaucrats, is good. With respect to the alleged Green governance, economical affairs, energy prices, in all these matters we believe that our government cannot take care of the interests of the Czechs.

Our organization does not escape the problem of war in Ukraine. We're not on the side of Russia or the United States. We're against the war. We're behind the room. How can we solve this problem?

The Czechs are convinced they must halt sending weapons to Ukraine. We believe that we can aid in a different way, e.g. deliver goods, food, supply medical care and another things, but not weapons. And only diplomacy can solve conflict. It can be said that in the present situation, for example, the Korean solution to the division of the country may be proposed to Russia. Let's say 1 January 2024. Borders will be set, war will halt and peace will be made. And both Russia and Ukraine will accept it and halt fighting. And Europe can organise the reconstruction of Ukraine."

The Czechs are tired of the war. They do not want to bear the costs of supporting Ukraine, they would like peace, although they do not truly realize the functioning of the Russian imperial machine. Peace with the Kremlin can't be sustained erstwhile the Kremlin feels the weakness of the another side.

Attention should besides be paid to the activities of Russian impact centres. Negative stereotypes about Ukraine and Ukrainians have been established, utilizing real but individual cases to illustrate the situation in the affected country. The scale of corruption is being exaggerated, the cost of military assistance to the populations of assisting countries to reduce the level of readiness to support Ukraine. any of the stereotypes break into the general Czech society.

Many Czechs are linked to the deteriorating economical situation with the war and the costs of Ukrainian aid. Among the participants of fresh protests is the belief expressed in an interview by Jana Markova, Czech blogger and activist [28]:

“In my opinion, the war in Ukraine is, of course, evil. What happened – Russia's attack on Ukraine – is completely unacceptable. There's nothing to discuss. But what we're doing is wrong, too, due to the fact that we're giving money for something, and we don't know where those millions of crowns, dollars, euros are, we don't know what they're meant for, and we have the belief that no 1 can control what's going on with that money. Well, if we give Ukraine any weapons or something like that, we may be able to get any control, but in the newspapers all day you can read how much corruption in Ukraine is. Our government then draws more and more money from our citizens. We don't have money for our pensioners, they took money to pay rent. Our pensioners don't get the rise they should get, and we send the money to Ukraine. Why? We don't know why. That's the problem.

They said we were Putin's agents if we rebelled before giving money to Ukraine. No, I don't want to give that money to Ukraine. It's my money and I want to know what's going on with them...

The comic thing is, our country borrows money from banks, due to the fact that although we pay advanced taxes, the budget doesn't close. And we're giving Ukraine. We besides give her guarantees for her loans. And if Ukraine doesn't return the money, we'll gotta pay for their debts. This is crazy.”

Contrary to concerns about the ubiquitous corruption in Ukraine, the arms supplied to Ukraine are utilized on the front. The Czech Danes attack Russian positions, ammunition is transported and used, and the defence of the Ukrainian army – alternatively of falling apart due to corruption – has been going on for the second year.

Control over the funds transferred to Ukraine's assistance should be improved, but not only should this support not be limited, but besides increased. There must besides be stronger political and economical force on the Kremlin. Only an assertive, tough attitude can discourage the Kremlin from continuing its conquest policy.

The Czechs who are so burdened with Ukraine's aid should remember that the policy of concessions from Western states at the expense of Czechoslovakia did not halt Berlin from escalating further demands, and consequently those French who did not want to die for Sudeta and then went to demonstrations against France's participation in the “Behind Gdańsk” war had to die in 1940 in defence of Paris...

Is present an unwillingness to send a fighting weapon Ukraine does not match those pro-peaceful Frenchmen from the 1930s? What happens if Russia attacks again erstwhile it is territorially and demographically reinforced? Another effort at peace at all costs? Well, that attitude will only encourage the Kremlin to proceed its acquisition.

I don't want to live to see the time erstwhile they're going to Warsaw, Bratislava and Prague, and from Berlin and Paris, alternatively of soldiers and tanks, they'll send us powdered milk and chocolate. Poland and the Czech Republic disagree from Ukraine, that our countries are fortunately further distant from Russia, but unfortunately this may change soon.

Unlike any of my Czech friends, I share the view of those analysts who advise to increase NATO's activities now and to expel Russian troops from the internationally recognized borders of Ukraine. The suppression in the embryo of expansionist, revisionist illusions prevalent in political elites The Kremlin will reduce the cost of defence against Russia in the future. Russia is afraid of specified a scenario, and that is why it is trying to influence our societies, weakening their will to defy evil and undermining attitudes called moral gambling. Unfortunately, Polish society is not free to influence anti-Ukrainian temper manipulation. The environment that wants to spoil the Polish Ukrainian relations, which consider themselves anti-establishment, focuses on what it shares, uncovering contradictions and making them medial, despite what facilitates the manipulation of Kremlin actions aimed at weakening sympathy for Ukraine and Ukrainians in Poland.

Ukraine's effective assistance in the fight against Russian aggression will only be possible if it has the support of most societies of supporting countries. Politicians are reluctant to engage in activities creating political immkovist not profit. The governments of Poland, Ukraine and the Czech Republic, observing the improvement of anti-establishment movements, can jointly prepare actions to counter the growth of anti-Ukrainian moods. The increase in anti-Ukrainian sentiments in neighbouring countries can besides affect the evolution of attitudes in Polish society, citing neighbouring experiences, imitating attitudes is common in Poland. The enquiry into the power of politicians in the countries of Central Europe which explicitly advocate a regulation or a complete withdrawal of the assistance of the fighting Ukraine will increase the safety costs for Poland, at last, represents a vital threat to the Polish state's right.

Mariusz Patey

Footnotes:

[1] Witold Biernacki, White Mountain 1620, Gdansk 2006.

[2] Adam Christmas, Poles and Rusini on the Slavic Convention in Prague in 1848, ‘Historica. Revue pro Historia a Příbuzné Vědy’ 2016, No. 1.

[3] https://jejeje.pl/updates/prof-t-cegielski-affili-departure-slowian-1848-ahead-his-epoke (accessed 28.10.2023)

[4] Jaroslav Šajta, Revoluční year 1848: Svatodušní bouře v Praze vypadaly v evropském srovnání spobtained from: https://www.reflex.cz/clank/history/874188/revolucni-rok-1848-svatodusni-boure-v-praze-vypadaly-v-evropskem-srovnani-spis-as-selanka.html (accessed 28.10.2023)

[5] Marek Kazimierz Kamiński, Polish-Czech conflict 1918–1921, Warsaw 2001.

[6] Zdeněk Kárník, České země v éře První republic (1918–1938), pp. 1–3, Praha 2000–2003.

[7] https://history.dorzeczy.pl/second-world-war/93739/stand-in-in-praga.html (accessed 28.10.2023)

[8] Norbert Wójtowicz, Nástup communistej dictatúry v Československ from pohľadu Poľska [in:] Február 1948 a Slovensko (Zborník of the Vedeck Conference, Bratislava 14–15 február 2008), ed. Ondrej Podolec, Bratislava 2008, pp. 63–83.

[9] https://observatorgospodarczy.pl/2022/11/27/economy-chech-i-Polish-comparative-two-sidings/ (accessed 28.10.2023)

[10] Milan Smerda, Czechs and Polish-Austrian relations between 1648 and 1795obtained from: http://wtmh.sobotka.uni.wroc.pl/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Sobotka_38_1983_4_505-516.pdf (accessed 28.10.2023)

[11] https://www.sbc.org.pl/dlibra/publication/198639/edition/187264/content (accessed 28.10.2023); "The increase in the participation of non-Saxon parts of society in active cultural and political life was faster and stronger in the Czech Republic than in Poland. The modern national movement in Czech countries was divided into German and Czech parts. In fact, the Czech part was limited to burgherhood, intelligence, and agrarian people, and only individuals came to it from the nobility. In this way, the Czech, modern national movement has gained the burgher and plebeic character from the beginning. It was completely different in Poland, where the nobles formed almost the tenth part of the nation, which was the highest percent compared to the nobles of another European nations. On the another hand, the percent of bourgeoisie – if not counting Jews who were in a peculiar situation – was smaller. In this state of affairs, the agreement between the 2 national communities was not easy, especially erstwhile Austrian bureaucracy was shortly active in relations between them, trying to usage Czech officials in Galicia as tools for its Germanization and oppression policy."

[12] Lech Wyszczelski, Zaolzie 1919–1938, Masovian Fires 2022.

[13] Jerzy Roszkowski, An act of baseless annexation or "historical justice". Polish border corrections with Slovakia in 1938, ‘Orawski Yearbook’ 2011, p. 3, p. 70.

[14] https://history.interia.pl/kartka-z-calendar/news-20-August-1968-r-people-military-Polish-participants-in-stlum,nId,1486621 (accessed 28.10.2023)

[15] Mirosław Szumiło, Press propaganda in Czechoslovakia to NSZZZ "Solidarity" on the example of "Rudé Právo" (1980–1981), ‘Res Historica’ 2022, t. 53, pp. 603–630.

[16] Jan Walczak, Lower Silesian Higher School of Entrepreneurship and Technology in Polkowice Solidarity of Polish-Czechoslovak (SPCz). Cooperation of the anti-communist opposition from Poland and Czechoslovakia from 1978 to 1990obtained from: https://depot.ceon.pl/bitstream/handle/123456789/4876/J_Walczak_Solidarnosc_Polish-Czechoslovacka_(SPC)._Wspolparaca_opposition_anti-communist_z_Polish_i_Czechoslovation_w_years_1978_-_1990.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed 28.10.2023)

[17] Dusan Janak, Tomasz Skibiński, Radosław Zenderowski, Conflict, rivalry, cooperation in Central Europe in the 20th–XXth century. Meanders of Polish-Czech relations, Warsaw 2021.

[18] https://businessalert.pl/Czech-trump-graza-orlen-resolution-elections/ (accessed 28.10.2023)

[19] Luboš Palata, Petr Fiala. Who is the fresh head of the Czech governmentobtained from: https://www.dw.com/en/petr-fiala-kim-is-new-chief-Czech-r%C4%85du/a-59967670 (accessed 28.10.2023)

[20] https://www.rp.pl/politics/art37861361-whom-is-petr-pavel-new-president-Czech (accessed 28.10.2023)

[21] David Bullock, The Czech Legion 1914–20, Oxford 2009.

[22] Peter Eberhard, The geopolitical views of Tomasz Masaryk. The geopolitical concepts of Tomas Masaryk, ‘Geographical Review’ 2017, Vol. 89, No. 2, pp. 319–338, was obtained from: https://rcin.org.pl/dlibra/show-content/publication/edition/63061?id=63061 (accessed 17.10.2023)

[23] https://defence24.pl/geopolitics/cheech-w-w-explosion-ammunition-is-only-one-version (accessed 28.10.2023)

[24] https://cvvm.soc.cas.cz/en/press-releases/political/international-relations/3829-opinons-of-the-chech-public-toward-the-events-on-Ukraine-april-2014 (accessed 28.10.2023)

[25] https://www.pism.pl/publications/Cryzys_relation_Czech-Russian_seven_year_after_explosion_in_Vrbticach_ (accessed 28.10.2023)

[26] https://www.polsatnews.pl/newsc-amp/2023-09-17/praga-anti-government-demonstration-in-the-table-what-streets-passed-10-thousand-persons/ (accessed 17.10.2023)

[27] https://abcniepodleglosc.pl/opinie/intelligence-with-mark-zeman-Czech-politics-involved-in-protest-against-current-authorities/mariusz-patey/6456 (accessed 28.10.2023)

[28] https://abcniepodleglosc.pl/opinie/intelligence-from-jana-brand-Czech-social activist/mary-patey/6452 (accessed 28.10.2023)

Publications:

- https://www.pism.pl/publications/changes-we-wspol-work-regional-in-europie-central-from-Polish-perspective

- https://www.osw.waw.pl/en/node/29241

- https://www.polsatnews.pl/newsc-amp/2023-09-17/praga-anti-government-demonstration-in-the-table-what-streets-passed-10-thousand-persons/

- https://www.gasetarawna.pl/news/world/articles/9298482,anti-government-demonstration-over-prage.html.amp

- https://www.pap.pl/updates/news%2C1561844%2Cprotests-in-chech-in-demonstration-in-praga-could-participate-100-thousand

- https://i.pl/large-protests-in-center-pragi-even-100-thousand-anti-government-demonstrants/ar/c1-16819311?gclid=CjwKCajwyY6pBhA9EiwAMzmfwQbznGz66l5ollDEAiqYOAauZwH2o2QNu-DprFqkOtElNYBBpGBoC2L0QAvD_BwE

- https://www.money.pl/economy/early-protest-against-and-government-domagaj-sie-regulation-6820832297753440a.html

- https://ies.lublin.pl/comments/dezinformation-in-republic-Czech-operation-authorities-and-citizenships/

- https://cyberdefence24.pl/armia-i-service/chech-agent-kremla-placecil-celebrytom-za-dissemination-propaganda

- http://wtmh.sobotka.uni.wroc.pl/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Sobotka_38_1983_4_505-516.pdf

- https://www.parkiet.com/parkiet-plus/art19568531-as-Russia-disposal-se-impact-nad-weltawa

- https://www.omp.org.pl/article.php?article=369

- https://rcin.org.pl/dlibra/show-content/publication/edition/63061?id=63061

- https://defence24.pl/geopolitics/cheech-w-w-explosion-ammunition-is-only-one-version

- David Bullock, The Czech Legion 1914–20, Oxford 2009. .

- Milan Smerda, Czechs and Polish-Austrian relations between 1648 and 1795obtained from: http://wtmh.sobotka.uni.wroc.pl/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Sobotka_38_1983_4_505-516.pdf (accessed 28.10.2023)

- https://observatorgospodarczy.pl/2022/11/27/economy-chech-i-Polish-comparative-two-sidings/

- https://www.pism.pl/publications/complications_in_relation_Czech_z_Russia_

- https://www.parkiet.com/parkiet-plus/art19568531-as-Russia-disposal-se-impact-nad-weltawa (accessed 17.10.2023)