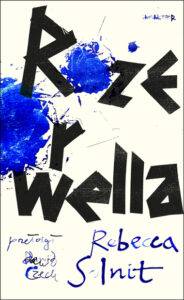

“Roses of Orwell” by Rebecca Solnit (in turn David the Czech Republic, Karakter Publishing House) is simply a wandering essay about the benefits of pleasure, frivolity and beauty “in a planet engulfed in confusion and troubled conflicts”, about hope in darkness. For “[if] the war has its opposite, it may sometimes be gardens.”

This is not George Orwell's biography, provided by Rebecca Solnit. His text calls “a series of intellectual wanderings beginning at the same point—from [...] the motion of the author planting respective rose bushes”.

In the spring of 1936, in Wallington, Hertfordshire, Orwell put rose shoots into the soil. Its roses proceed to grow there: “Two spready unbridled shrubs [...], 1 with mildly open pink buds, and the another with salmon flowers with a golden yellow border at the root of each petal. These more than eighty-year-old plants—living creatures planted with a surviving hand (and a shovel) of a man who could admire them only through a short long of their time of existence—still pulsed with life.”

Contrary to what Solnit writes, “Roses of Orwell” is simply a wonderful biography (bios – life), unanthropocentric and sylvalic. Like a “forest of things”, uncut, chaotic and overgrown garden. Although there are quite a few surprises in this book, I was certain that there would be a metaphor for rhizome. Solnit compares conventional stories about people to how to construct genealogical trees – elegant lineages, spread lines and gunners, while verifying Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari's findings: The 43-hectare axial poplar forest in Utah has late been considered a single organism, “the largest of the presently surviving on Earth and 1 of the oldest”. 40,000 clones connected by a common root system.

Solnit begins “Roses” with a confession (this is besides a test of reading autobiography): she returned to Orwell through the trees that are fascinated by documentaryist Sam Green. Eseist gave her friend Orwell's essay (which, by the way, calls "meandering prose", uncovering formal relatives) "Good words for pastor of Bray". Orwell, who has just planted apple trees – orange cots, tells about a “private afforestation programme” that can be attempted to buy back “any antisocial act”. Solnit resembles the Etruscan word saeculum, which means a 100 years: the age of the oldest man surviving at a given moment. It is simply a time period in which a given event can be called the 1 that occurred “for human memory”. It's apparent that trees have different saeculums than humans. From their perspective, human time is simply a flash. They're long-lived, they keep a memory of places.

Orwell's tree in Wallington was gone. But there were roses.

Roses: “Cichlers, undermining the profoundly rooted, conventional image of Orwell”.

How can orwellologists benefit from knowing about roses?

Solnit writes about literary returns. It is besides crucial to me – the texts read after years are different, due to the fact that they are richer about the experiences of their recipients. Prior to the end of his tour in the footsteps of Orwell, Solnit reads again "The Year 1984", revealing in it what is unobvious – alongside the large Brother, the thought Police, new-word or torture descriptions is in this fresh "the abundance of beauty and pleasure". With surprise (which I share with her), Winston is delighted by his 50 - year - old, worn - out workwoman body: “A massive, shapeless body akin to a granite block, with its rough reddish skin, so is simply a young girl’s body like the fruit of a chaotic rose to her flower. Why should the fruit be worse?”

“Roses” are an essay “travel” in respective meanings. Solnit moves in space (visiting e.g. the ghostly rose plantation in Bogota, the “ocular pleasance factory”) and in time (to carbon), keys on the sides of books and archives shelves. He writes about the roses of Tina Modotti and Stalin's lemons, he talks about Lysca, who wanted to turn wheat into rye and terrorizing nature. Orwell is portrayed here unrecognizably – Solnit reminds him of the boredom of political essayism, women's flotation and paternalist tone.

First of all, it is simply a book critical of anthropocene. Remembering Orwell's stories about the destiny of British miners, Solnit takes the reader in time travel to the carbon age – a sixty million years of inhaling plants that we have managed to destruct over the last 200 years. We're going through coal forests with immense forks and violins. Solnit writes: “It was an alien planet. It must have been tens of millions of years before the conditions for human evolution arose. There were no words or names on this Earth: many mute worlds arose on it, and then fell, 1 by 1 passing distant into oblivion, their tracks are covered by subsequent changes in geology, geography, biology, atmosphere composition and climate. We would not have recognized this planet and there was no place for us.”

I wrote down the words of Joe Lamb, a tree surgeon and poet, a friend of Solnit: trees are “catched by sunlight. [...] Even the most solid plants, specified as giant redwoods, are fundamentally only light and air.”

Image source: Nikita Tikhomirov

![Wręczali dzieciom 'opaski niezgubki’ [zdjęcia]](https://tkn24.pl/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/Opaski-niezgubki-2.jpg)